For hundreds of thousands of years, humans have inhabited Earth, shaping and being shaped by its landscapes. And yet, only in the past few centuries has a destructive narrative emerged – one that separates humanity from nature, romanticising the idea of a ‘wild’ and untouched world. This notion, which underpins modern conservation efforts, was built upon colonial violence, religious ideologies, and economic systems that sought to commodify the natural world. From the forced removal of Indigenous communities to create national parks to the glorification of ‘pure’ landscapes in art and photography, the myth of pristine nature has endured, reinforcing a harmful division between people and the environment. Understanding this history is crucial to dismantling it and forging a new relationship with nature – one that recognises human presence as integral rather than intrusive.

The idea of wilderness as an unspoiled paradise was largely a European (later American) invention, shaped by colonial expansion and the forced displacement of Indigenous peoples. Before the arrival of settlers, Indigenous communities across the world actively managed their environments through controlled burns, seasonal hunting, and sustainable agriculture. The landscapes that colonists perceived as ‘untouched’ were, in fact, deeply intertwined with human care and history.

John Muir, one of the most celebrated figures of the Western conservation movement, embodied this blindness to Indigenous history. Muir’s writings on Yosemite and Yellowstone, two of America’s first national parks, describe these landscapes as if they were pristine, untouched by human hands. He called them ‘temples’ and ‘cathedrals’ of nature, failing to acknowledge that they had been shaped and maintained by Native American stewardship for millennia. He wrote, "None of Nature’s landscapes are ugly so long as they are wild." But the ‘wild’ landscapes he described had been carefully managed by Indigenous people for centuries. The idea that nature was most beautiful when devoid of humans was not only a romanticisation but also a justification for their violent removal. The Ahwahneechee people, who had lived in Yosemite Valley for generations, were forcibly expelled so that white tourists could marvel at its ‘untamed beauty.’ Similarly, the Shoshone and other tribes who had long inhabited the Yellowstone region were driven from their land, their presence erased from the official narrative.

The removal of Indigenous people was not an unfortunate consequence but a fundamental part of the national park model. The U.S. government justified this under the pretence of ‘preserving’ nature, an idea deeply rooted in colonial thinking. As historian Mark Spence notes in Dispossessing the Wilderness, "the context and motives that led to the idealisation of uninhabited wilderness not only help to explain what national parks actually preserve but also reveal the degree to which older cultural values continue to shape current environmentalist and preservationist thinking." National parks became ceremonial landscapes, reinforcing colonial power structures while offering a pre-packaged, sanitised version of the wild for upper-class consumption.

Today, just over 56 million acres of land exist as Native American reservations. That is about two per cent of the ancestral Indigenous land that the United States occupies (and conditions in a lot of them are incredibly bad).

Stephen Corry, director of Survival International, has described this as the "creed of empty wilderness." He writes, "It was precisely because they were 'barely human' that their lands could be called uninhabited and pristine, and their territories then made uninhabited by chucking them out." He argues that conservation efforts have historically been built on the erasure of Indigenous people, a pattern that continues today in Africa and Asia, where local communities are evicted to create wildlife reserves for eco-tourism.

The Cloud Forest in Ecuador provides another example of this erasure. The Indigenous Quijos used to live there, but in the 16th century, they were first enslaved and then murdered by Spanish colonisers (1540s and then 1578). For 130 years, the forest stood without human presence; trees grew back over the once-inhabited places. But in the early 1800s, humans returned to the valley. They grazed animals and altered the mosaic of trees. However, in the mid-19th century, when European ‘explorers’ passed through, the forest seemed so dense and uninhabitable that they assumed it had never seen humans before. Therefore, they claimed the land to be pristine and wild, a harmful assumption that fuelled broader conservation policies which disregarded Indigenous knowledge and management practices.

The myth of untouched nature was also deeply intertwined with religious thought. The Bible’s Genesis describes humanity’s dominion over nature, reinforcing the belief that the natural world was created for human use, yet simultaneously sacred and separate. Protestantism, particularly in post-Reformation Europe, shaped this perception by framing nature as a divine space free from human corruption.

The Protestant Reformation’s rejection of Catholic monastic traditions, which had often emphasised sustainable land use, accelerated a shift toward land enclosure and privatisation. "The lords put peasants under heavy pressure to extract from the land and forests while giving nothing back," wrote historian Jason W. Moore. "This drove a crisis of deforestation, overgrazing, and gradual decline of soil fertility."

Thankfully, the political revolt that occurred after 1350 brought forth a period of ecological regeneration. Having control over their land, peasants managed to maintain a more reciprocal relationship with nature. However, after some time, the societal ‘upper class,’ consisting of the Church, merchants, and noblemen, worked to end peasant autonomy. They achieved this by forcing peasants off their land (dispossessing them was essentially a form of internal colonisation) and turning the remaining forests, pastures, and rivers into property. These lands became privatised, creating a commodity from them and allowing surplus accumulation. This also changed their role from something that used to sustain the people living there, people who lived harmoniously with it, to a pawn in a power struggle. Moreover, through the use of force, vast areas of nature became accessible only to the elites. In this case, not for their pleasure of admiring and revelling in it, but because it stopped being democratically available. And it wasn’t just a matter of fencing off the areas. Villages were destroyed, and crops were ripped up and burned. Thousands of rural communities were demolished into oblivion.

Over the next few centuries, many battles were fought by peasant communities who wanted their life resources back. During the same year as the peasant rebellion of 1525 in Germany, which single-handedly left more than 100,000 commoners dead, Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés slaughtered 100,000 Indigenous people as his army marched through Mexico and destroyed Tenochtitlan (the Aztec capital), for which King Carlos I awarded him the country's highest honour.

During the era of enclosure in Europe, peasants were granted temporary access to land based on the productivity of their labour, which meant they were pitted against each other in a fight for survival. This drastically increased the quantity of grain extracted between the 16th and 20th centuries. This increase was seen as an ‘improvement,’ justifying enclosures. John Locke argued that, even though enclosure was a theft, it was morally justifiable as it enabled a shift to intensive commercial methods, increasing total output, which contributed to the ‘greater good’ and the benefit of humanity. (This same logic was used to justify colonisation – improvement as an alibi for appropriation.) However, it was only the elites who benefited from the increased labour productivity while commoners endured two centuries of famine. Moreover, even though profits soared, workers’ wages actually decreased over time.

Nowadays, creating new land enclosures is still justified in the same way: ‘for the greater good,’ for ‘development and growth.’ Anything goes for growing the GDP.

Arthur Young: "Everyone but an idiot knows that the lower classes must be kept poor, or they will never be industrious."

Reverend Joseph Townsend: "It is only hunger which can spur and goad them on to labour. Legal constraint is attended with too much trouble, violence, and noise... whereas hunger is not only a peaceable, silent, unremitted pressure, but as the most natural motive to industry, it calls forth the most powerful exertions... Hunger will tame the fiercest animals, it will teach decency and civility, obedience and subjugation to the most brutish, the most obstinate, and the most perverse."

David Hume: "It is always observed, in years of scarcity, if it be not extreme, that the poor labour more, and really live better."

The situation was similar in the colonies. In India, to eradicate resistance to the demands of colonisers, the British imposed taxes so high that local peasants plunged into debt so grave they were left with no choice but to comply. Furthermore, they destroyed granaries, privatised irrigation systems, and enclosed commons that people used for wood, fodder, and game. The destruction of communal support systems led to a famine at the end of the 19th century, so great that it killed 30 million Indians.

In South Africa, displacing people off their land pushed the Black population onto just 13% of the country’s territory (the Native Act in South Africa). Taking over the land to create enclosures played out similarly in the Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, and French colonies.

Romanticism and the Myth of Eden

Alan Braddock wrote, “Art has the power to help us understand these issues (ecology) and inform our ethical and moral decisions. It also alerts us to issues of environmental justice and ecological inequity, since not everyone perceives places and conditions in the same way.”

The romanticisation of ‘wild nature’ began alongside the early colonisation of North America. In the 16th century, paintings intended to attract settlers depicted lush landscapes as the backdrop for portraits of wealthy colonists. Their goal was to craft an image of a promised land, a land abundant with resources, an Eden on Earth.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, European classical landscape paintings continued this narrative, portraying nature as an idyllic, harmonious realm, often drawing inspiration from Arcadian mythology—a legendary place in ancient Greece known for its pastoral beauty. Every tree, mountain, and river was meticulously placed to create an idealised version of nature, one that appeared aesthetically perfect, yet artificially constructed. This portrayal perpetuated the idea that nature, to be celebrated, must be controlled by humans, and shaped to suit their desires. At the same time, it conveyed that nature is a fairytale paradise, a heaven, requiring human intervention to form, yet not everyone was ‘deigned worthy’ to enter it. Landscaped gardens, for example, became a luxury available to the elite, not for their enjoyment, but to serve the needs of others.

The Protestant Reformation shifted artistic focus toward vast, untamed landscapes. Dutch painters like Jacob van Ruisdael depicted dramatic skies and windswept forests, reinforcing the idea of nature as raw and overpowering. The beauty of nature became a form of worship, with people shown as small and insignificant against the grandiose landscape. As an audience, we were meant to step back in awe and worship, but not find our place within it. This divide between humanity and nature is a dangerous one because once we treat ourselves as separate from nature, it becomes easy to dismiss our responsibility to empathise and recognise the power dynamics at play.

Meanwhile, the 19th-century American Hudson River School glorified the ‘sublime’ wilderness of the West, often erasing signs of Indigenous habitation. “In the late 19th century U.S., after the ‘Indian problems’ had been brutally solved and the frontier ceased to exist, a veritable Cult of Wild Nature flourished. Throughout the 19th century, Americans idealised nature through a ‘pastoral’ or semi-primitive lens. ‘Raw’ nature was not in itself something to worship, but its potential under human care seemed limitless. Human progress was measured through nature’s domestication,” Deborah Bright notes in Of Mother Nature and Marlboro Men.

The rise of photography further solidified the myth of wild nature. Ansel Adams, one of the most famous American landscape photographers, captured images of Yosemite that became iconic representations of ‘pure’ wilderness. Yet these images obscured the reality that Yosemite had once been home to Indigenous communities who were expelled to make way for white visitors. Adams didn’t necessarily aim to disregard the long history of the places he photographed, but his work nevertheless reinforced the myth of vast, natural expanses untouched by people.

The concept of the national park as a museum-like space persists today. Landscapes are conceived as “wholesome subjects for middle-class audiences.” They are spaces of recreation for those who can afford access, while Indigenous people remain excluded. “Thus, whatever its aesthetic merits, every representation of landscape is also a record of human values and actions imposed on the land over time.”

Nature was marketed as an escape from urban life, yet it was being shaped for middle-class tourism, with railroads and automobiles making it more accessible. These landscapes were, and still are, ceremonial in nature, requiring a code of personal conduct (park rules and regulations) and ritualised expressions of devotion (pilgrimages made on certain holidays). These imposed rules and emotions we are expected to abide by shape how we experience 'untouched, raw' nature.

Rather than seeking untouched wilderness, tourists sought dramatic, picturesque landscapes that aligned with pre-existing imagery from postcards, paintings, and media. National parks were carefully designed to conform to aesthetic expectations, reinforcing a structured, commodified experience of nature. In 1908, 69,000 tourists went to worship in the eleven national parks. Twenty years later, the figure had climbed to three million.

The Western landscape, especially through cowboy films, was further mythologised as a rugged, masculine domain, strengthening the idea of nature as a place of heroic struggle. “In the American consciousness, the Western landscape has become a complex construct. It is the locus of the visually spectacular, culled from the total sum of geographic possibilities and marketed for tourist consumption. For liberal conservationists, it represents the romantic dream of a pure, unsullied wilderness where communion with nature can transpire without technological mediation–a dream that has been effectively engineered out of modern experience.”

Over time, wilderness became a marketable product: camping fees, guided tours, and vacation packages turned nature into something to be consumed rather than deeply engaged with. Access to the outdoors was dictated by urban work schedules, reducing genuine connection to the land. “Nature has become commodified, its benefits bought and sold in the form of camping fees, trail passes, equipment, and vacation packages at wilderness resorts.” As J.B. Jackson notes, “We come into contact with Nature on a tight, highly structured schedule-holidays and weekends-which is determined not by the change of seasons, but by the routines of urban work.” This nature has been designed to help us absorb its benefits as efficiently as possible. Park displays ensure that we are exposed to the peak experiences at the site, the sights. This separation between humans and nature fostered detachment, making exploitation easier.

During the 1940s and '50s, Adams portrayed the American wilderness as a pristine and timeless paradise, a vision that aligned with the era’s conservative values. At the same time, the U.S. was embracing its role as the leader of the "free world" in the Cold War, reviving the spirit of Manifest Destiny. This glorified perception of nature was widely circulated through Sierra Club publications, featuring the work of Adams, Eliot Porter, and others. The framing of these images dictated how people experienced nature, making it feel almost sacred. With art and media shaping public perception, there is a responsibility to present nature in ways that don’t reinforce harmful myths or disconnect people from the reality of environmental issues.

Rethinking wilderness

The idea of ‘wild nature’ as something separate from humanity is a racist and colonial construct—one that has justified the erasure of Indigenous communities, shaped restrictive conservation policies, and distorted our perception of the environment through art and media. From John Muir’s vision of sacred wilderness to Adams’s pristine landscapes, this myth has been carefully curated and reinforced for centuries.

To move forward, we must dismantle this narrative. Nature is not something to be observed from a distance; it is something to be lived within and cared for. By embracing a more inclusive vision of the environment, one that acknowledges human presence as essential rather than intrusive, we can foster a truly sustainable relationship with the natural world.

“Conservation has to stop the illegal eviction of tribal peoples from their ancestral homelands. It has to stop claiming tribal lands are wildernesses when they’ve been managed and shaped by tribal communities for millennia. It has to stop accusing tribespeople of poaching when they hunt to feed their families. It has to stop the hypocrisy in which tribal people face arrest and beatings, torture and death while fee-paying big game hunters are actively encouraged.”

Stephen Corry

In contrast to the colonial tradition of depicting landscapes as pristine and uninhabited, contemporary artists are actively deconstructing this narrative.

Kent Monkman, a Cree artist, reclaims Indigenous perspectives by subverting the grand American landscape tradition. His paintings, such as The Daddies, challenge the works of white artists like Robert Harris by appropriating his painting Meeting of the Delegates of British North America to Settle the Terms of Confederation, Quebec, October 1864, subverting Canada’s political history by imposing a queer and Indigenous presence on the origins of Confederation. In other works, he exposes how idyllic wilderness scenes erased Indigenous communities entirely and introduces a new narrative reclaiming the agency of First Peoples. Monkman’s alter ego, Miss Chief Eagle Testicle, appears in many of his works, disrupting the romanticised notion of the untamed West and inserting Indigenous agency back into the frame.

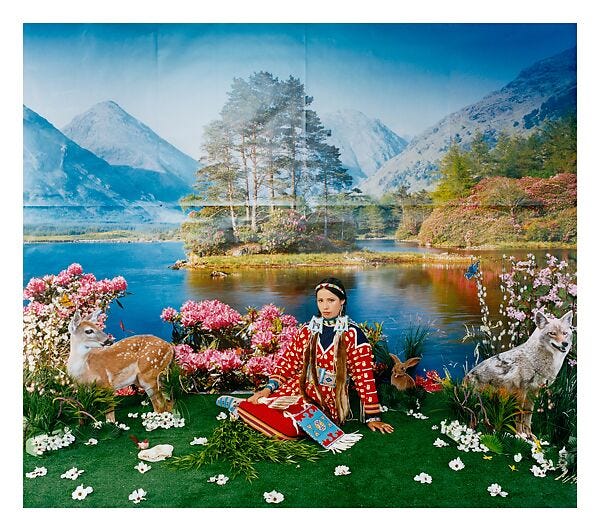

Wendy Redstar, a member of the Apsáalooke (Crow) Nation, also interrogates the colonial gaze. In her Four Seasons series, Red Star poses in dioramas with inflatable animals and artificial materials, humorously challenging the boundaries between authenticity and stereotypical portrayals of Native subjects. Her portraits encourage reflection on the ingrained stereotypes of Native Americans in popular culture. By staging herself in artificial scenes, Red Star evokes Cindy Sherman’s Untitled Film Stills, referencing Hollywood B movies. While Sherman explores feminine stereotypes through changing disguises, Red Star focuses on her identity as an Apsáalooke woman, highlighting the challenges Native women face in the art world.

In another series, My Home is Where My Tipi Sits, Red Star creates a grid of five distinct elements from Crow Reservation life: brightly coloured government houses, broken-down “rez” cars, sweat lodges, signs, and churches. Through large, vibrant photographs, the series pairs a title based on a Crow chief’s poetic phrase with the everyday visual markers of life on the reservation. Drawing on the Bechers' approach to photographing industrial structures in grids, Red Star honours their conceptual style while complicating the formality of the grid. The work critiques the historical under-compensation of Native peoples for land loss and the realities of reservation life, using the grid as an unsettling reference to class. Red Star's series subverts Western approaches to ethnography, privileging Native perspectives and creating a visual narrative that resists the usual classification of Native lifeways.

Valerie Hegarty takes a different approach by physically distorting the very landscapes that shaped America’s conservation narrative. Her piece Fallen Bierstadt depicts a crumbling version of Albert Bierstadt’s romantic paintings of Yosemite, symbolising the unravelling of the pristine wilderness myth.

Today, a new wave of artistic and scholarly inquiry is challenging these established narratives. Through the work of contemporary artists and ecocritical scholars, the intertwined histories of colonialism, conservation, and art are being re-examined. By reintroducing Indigenous perspectives and exposing the constructed nature of our environmental ideals, these voices are paving the way for a more inclusive, equitable, and sustainable vision of our natural world.

The wild we see is not an unblemished canvas; it is a palimpsest of human history, marred by colonial violence and replete with stories of survival, resilience, and stewardship. To honour this complexity is to acknowledge that nature, far from being a museum piece to be admired from a distance, is a living tapestry in which every human being has a role. Only by embracing this interconnected vision can we hope to forge a truly sustainable future. One where the legacies of the past inform a more just and harmonious relationship with the Earth.

Further resources:

Of Mother Nature and Marlboro Men, by Deborah Bright (1985)

Viewing the Archive: Timothy O'Sullivan's Photographs for the Wheeler Survey, 1871-74

Killing conservation – the lethal cult of the empty wild

The Story We’ve Been Told About America’s National Parks Is Incomplete

Nature Wars, Culture Wars- Immigration and Environmental Reform in the Progressive Era

Nature's Nation: American Art and Environment

Art in American Colonies and the United States, c. 1700–1865

Dispossessing the Wilderness Mark David Spence

Such an incredible piece, thank you for writing and sharing.

Love, love, love!