In the second half of the twentieth century, as New York cemented its status as the gravitational centre of American art, a quieter, more expansive visual language was emerging on the opposite coast. Los Angeles - horizontal, diffuse, self-consciously artificial - offered a counterpoint to Manhattan's vertical intensity and commercial saturation. Two artists in particular spring to mind when thinking of the visuality of LA. Both born in 1937, and both coming from other places, Ed Ruscha and David Hockney fell in love with the city and dedicated their lives’ work to it. The two men share a fascination or preoccupation with the quotidian. Working with themes naturally occurring in their lives, neither of their bodies of work feels forced, but seems to be a natural extension of the artists and their lives.

Ruscha, an Oklahoma transplant, mapped the surfaces of LA with a deadpan conceptualism rooted in signage, topography, and typography. While Hockney, a Yorkshire émigré, found in Los Angeles an Arcadian sensuality, in the sunlight diffused across swimming pools and lovers’ bodies, that recalibrated his painterly language. Together, these artists developed a dual portrait of the city and its ethos: Ruscha through irony, estrangement, and linguistic flatness; Hockney through affection, luminosity, and perceptual experimentation.

Hockney found himself enamoured by LA’s light, bright colours, the pools, the lawns, and its sense of freedom. It had an openness and casual sensuality or eroticism, even, which was absent in England. Moving at 26 from post-war England, America was almost a promised land, and Los Angeles was the epicentre of liberalism and bohemia. In an interview, he said that it was three times better than he’d imagined, he called California sexy and said that people have more joy in the sun. And that’s what his paintings are: they are joyful. Sundrenched, vibrant, full of life, youth, sex, fun. His repeated depiction of male nudes, swimming pools, and moments of intimacy reclaims the visual field as a space of homoerotic celebration. In contrast to Ruscha’s depopulated landscapes, Hockney’s L.A. is populated by bodies that desire and are desired.

Ed Ruscha, on the other hand, discovered LA at the age of 18, during a road trip. He travelled out West after feeling the need for a change. Los Angeles immediately cast a spell on him. He later described it as having “an almost narcotic effect” on him: fast, slick, and swanky, it “twinkled and sparkled” with an allure that was both superficial and magnetic. He enrolled at the Chouinard Art Institute (now CalArts), marking the beginning of a lifelong relationship with Southern California. Throughout his life and to this day, Ruscha has explored its visual and linguistic landscape.

Ruscha’s early photographic practice emerged organically from this environment. His seminal Twentysix Gasoline Stations (1963), one of the most influential artist books of the twentieth century, consists of black-and-white photographs taken during his road trips across the American Southwest. They are deliberately crude, fast, and unstudied. Ruscha was drawn to the architectural quality of the stations: the repetitiveness, symmetry and the canopy extending out from the building, creating a dynamic composition. He embraced the aesthetics of the snapshot: anti-compositional and anti-expressive, resisting the photographer’s traditional role as interpreter.

Viewing his photographs as a diary, he recorded subjects both visually stimulating and emblematic of the psychological and cultural landscape. Gas stations, palm trees, signs, and swimming pools. The latter is probably the most iconic and recognisable of Hockney’s works. For Hockney, the pool is a site of sensual immersion, in which the surface and depth are in constant tension. But the pools in Ruscha’s photographs were not slick, bright and inviting. They appear vacant, liminal and slightly unsettling.

Appearing in Nine Swimming Pools and a Broken Glass (1968), the pools seem deserted. In most images, the water is still, rippled gently only by the wind, except for one, in which it looks ruptured by the impact of a diver, yet there is no one to be seen. There is evidence of a presence, now vanished completely but for its trace.

Ruscha’s photographs of pools portray an estrangement of American life. They evoke what Marc Augé calls “non-places” - spaces of transience, unrooted from personal or communal memory.

In contrast, for Hockney, in works like A Bigger Splash (1967), the water becomes a symbol of both visual and physical pleasure. Painted with obsessive attention to texture, Hockney’s pools shimmer with desire. The subject in this painting, too, is invisible - submerged or vanished - but the emotional resonance is palpable. Where Ruscha’s pools evoke liminality and absence, Hockney’s evoke pleasure and presence through the traces of touch, movement, and erotic tension.

For Ruscha, L.A. is a system of signs without referents; its commercial vernacular (billboards, gas stations, signage) is divorced from meaning, language drained of intention. Hockney, conversely, reads the city as a phenomenological playground, where light, touch, and visual pleasure generate meaning in excess of representation.

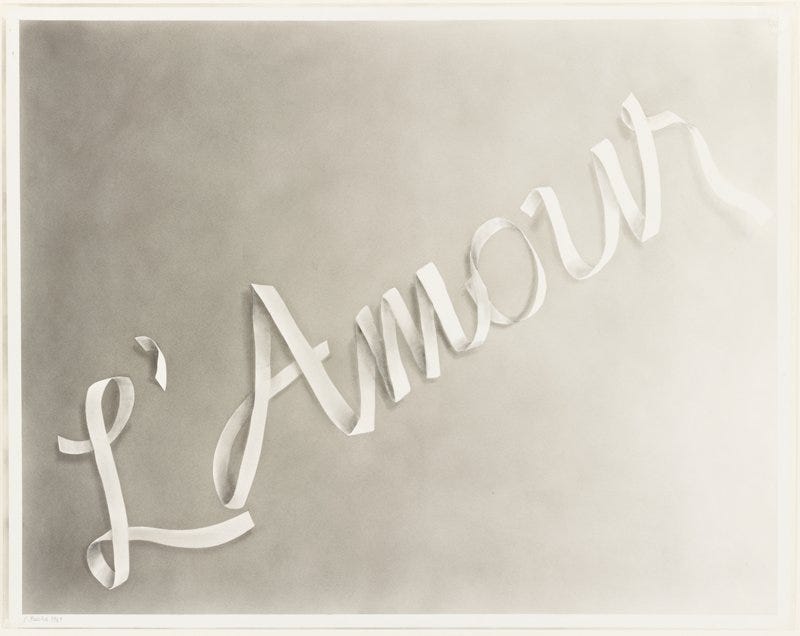

If Hockney and Ruscha both mapped the surface of Los Angeles in their own ways, their approaches to meaning and perception diverge more sharply in how they each grapple with language. For Hockney, the problem was how to represent seeing itself: how to break apart linear perspective, to acknowledge the mobility of the eye, the time it takes to look, and the subjective distortions of memory and feeling. For Ruscha, on the other hand, language was something more abstract, something visible, sculptural, yet always elusive in meaning.

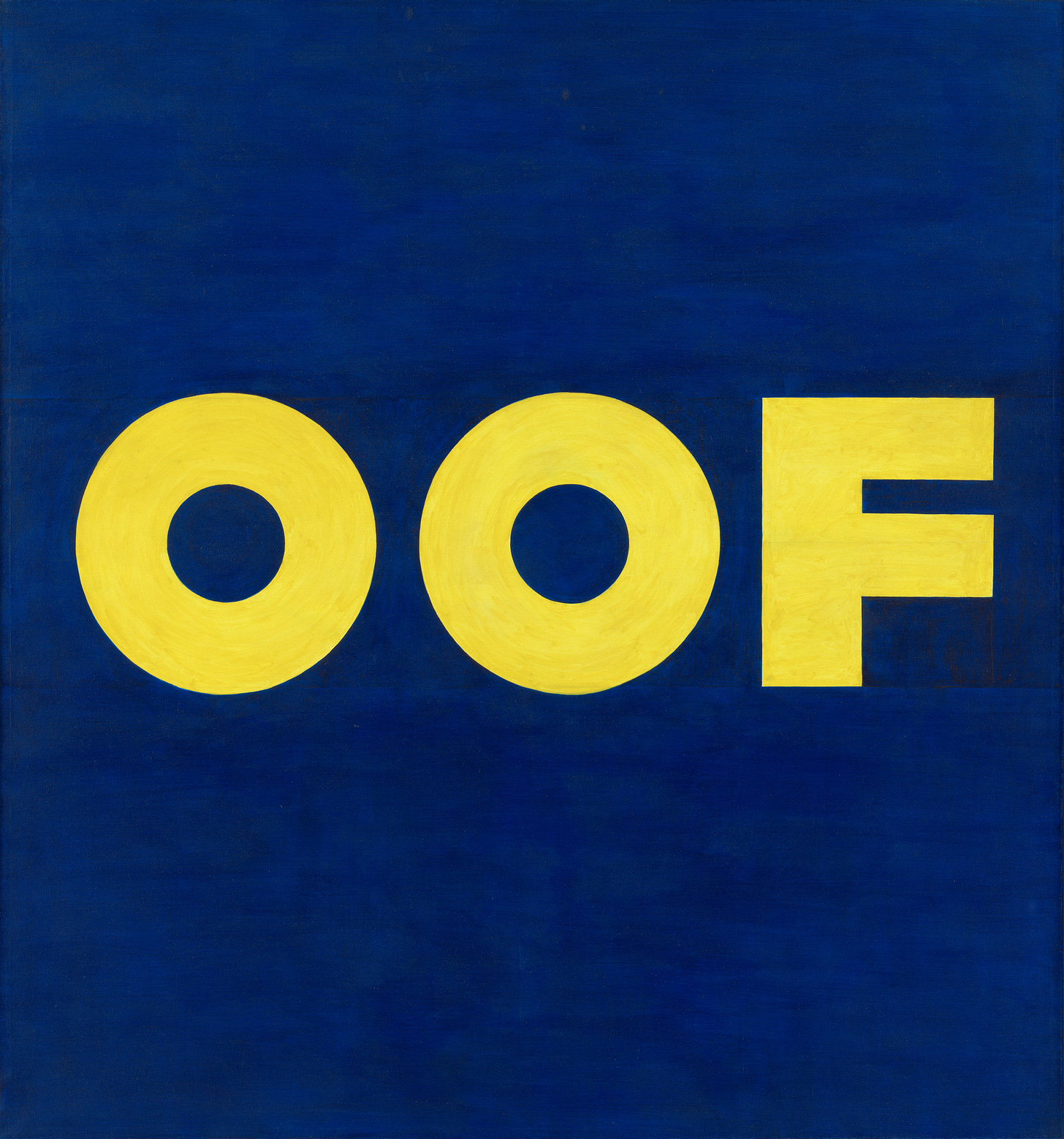

Ruscha’s engagement with text is well known: single words suspended in space, smoothly applied over gradients of colour or painted in flat block letters across canvas. Words like “OOF,” “HONK,” or “SMASH” – onomatopoeic, graphic, open-ended. One can almost hear them by just looking at the works.

“The single word, its guttural monosyllabic pronunciation, that’s what I was passionate about. Loud words, like slam, smash, honk.”

They are sometimes banal, sometimes vaguely threatening. Ruscha’s words function less as communicative devices than as visual units, abstract shapes that flirt with legibility. He once said, “I have always operated on the idea that my work is essentially a collection of readymades,” and in this sense, language, for him, becomes just another object. The words in his paintings are almost just a collection of shapes, which happen to have been given meaning by humans. His use of simple, clean fonts heightens the sense of abstraction those words carry.

Emerging in the postwar era of mass consumerism, the Cold War, and the Vietnam War, Ruscha’s deadpan engagement with language, signage, and commercial iconography undercut the ideological promises of American modernity.

His use of banal phrases, floating words, and depopulated architectural motifs mimicked the language of advertising, but stripped them of any persuasive content. In doing so, he revealed the hollowness at the heart of the spectacle. Ruscha’s aesthetic of affectless repetition and ambiguity mirrored a cultural landscape saturated with images but starved of meaning. His work, still today, continues to expose the vacuity of consumer culture and the alienation of the American West, and maybe even the unease beneath postwar optimism.

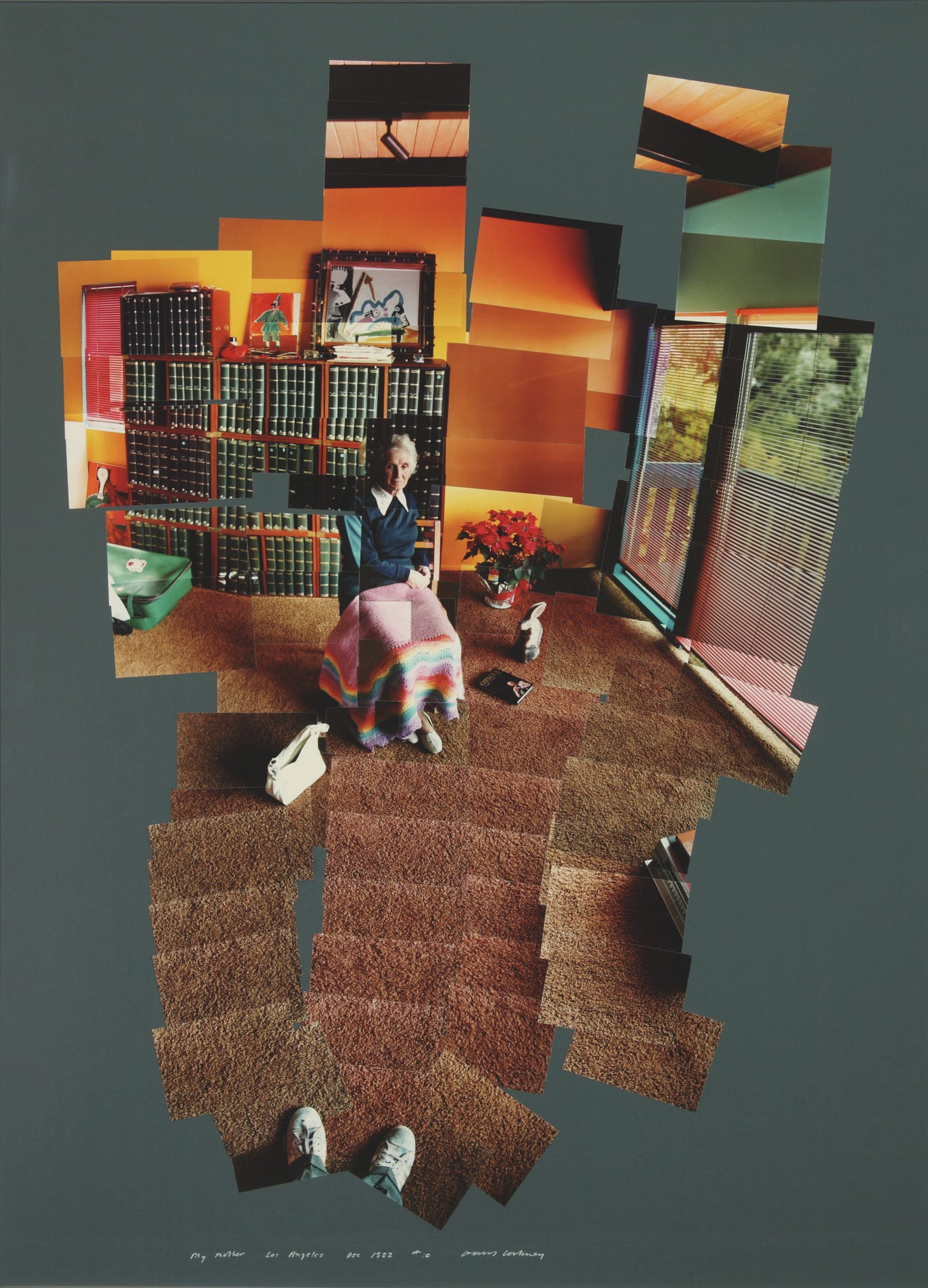

Hockney, by contrast, rarely incorporates text into his visual work, but is deeply concerned with the act of seeing. His experiments with perspective, in paintings, drawings, and especially Polaroid collages, attempt to resist the single, fixed viewpoint inherited from Renaissance painting and reinforced by the camera. In works like the well-known Pearblossom Hwy., 11–18 April 1986, #2, a panoramic collage of photographs taken from slightly different angles and moments in time, Hockney pieces together a composite way of seeing: fragmented, layered, and temporally stretched. He once said about the traditional use of photography that “photography is all right if you don’t mind looking at the world from the point of view of a paralysed Cyclops,” and his own work pushes back against this monocular, mechanical gaze.

Andy Grundberg, writing about Hockney’s photographs, noted that the artist was reacting against the “tyranny of the single point of view” that had come to dominate both photography and painting. The camera, Hockney believed, offered a false kind of objectivity, reducing vision to a mechanical gaze. In contrast, the so-called joiners (collages of polaroids or prints) reflect how we actually see: piecemeal, mobile, subjective. Grundberg described them as "a cross between Cubism and cinematic montage," and indeed, they often echo both in their fragmentation and their rhythm. In works like Mother, Los Angeles Dec. ’82, Hockney approaches his subject from multiple angles, including her, the room, the view outside the window, all within the same temporal field. The resulting image is an attempt at a deeper immersion in the reality or moment portrayed.

Grundberg, again, points out that “the very fragmentation of the joiners makes them more faithful to experience than any single photograph could hope to be.” They are more truthful precisely because they do not pretend to be neutral. They openly announce their subjectivity, and, in fact, portray not only what’s in front of the camera but the act of looking itself. They remind us that vision is not passive but participatory, and that our understanding of the world results from piecing together many fragments of what we see and experience.

So while Ruscha flattens and stills language into a visual object, often stripped of context or obvious emotion, Hockney tries to open up vision itself, allowing it to expand and contract, to hold multiple positions at once.

Though drawn to Los Angeles for similar reasons, its light, openness, and sense of possibility, Hockney and Ruscha developed different visual languages. Together, their work reflects the city’s dual nature: both emotional and affectless, seductive and estranged, a site of pleasure and of critique. In mapping its surfaces through such contrasting lenses, they helped define the visual imagination of postwar Los Angeles.